Where have all the insects gone?

As a child, it was always my job to remove moths from my big sister’s bedroom. They were common visitors then and she was terrified of them, especially the big furry white moths which would flicker around the light and bang themselves off the window panes, probably puss moths. I would gently cup them in my hands to ease them out the window again (but not before pretending to throw them at my sister, which was always met with fearful squeals). I don’t see those big furry white moths indoors any more.

Another common occurrence was cleaning bugs off the car windscreen – how after a long car journey, our parents would have to stop and clean off the windscreen, having accumulated the remains of lots of dead insects.

Have you noticed this doesn’t happen any more? At least not where I live, in the midlands. Last summer, we took a trip to West Donegal and after the last leg of that journey – through the more remote countryside in the west – we did indeed have to clean the windscreen to improve visibility, and it reminded me of how regularly you would have to do this 20 or 30 years ago.

These may seem like strange insect-focused nostalgic tales of my youth – like when it was always sunny in the summer and we had snow every winter – but is there any more to it?

Recent research from Germany, published in the journal Plos One, highlights a severe collapse in flying insects. The German entomologists found that three-quarters of flying insects had vanished in the last 27 years. But what was most telling about this research was that these extreme losses were measured in nature reserves. While one might expect insect losses in localized areas, on highly intensive farmland or in urban centres, it was shocking to see that even in nature reserves – which we like to tell ourselves are our refuges for our wild species – even here, biodiversity is under threat.

We have known about what we call the sixth mass extinction for a long time. Indeed, we have perhaps become desensitized to news stories about the last Rhino or threatened Polar Bears, those charismatic large mammals that have been used as flagship species for conservation programmes and environmentalism. And if we can’t prevent the loss of gorillas or tigers – due to habitat loss and an exploding human population – how would ecologists convince people of the importance of an insect? People tend not to like insects anyway. So why would they care about the loss of flies, midges or wasps or mosquitoes? But perhaps this massive widespread loss in our insect populations shows something even more disturbing and sinister in how we are changing the planet on such a broad scale. And perhaps this is the type of research that might make decision-makers sit up and take notice.

It is important to note that insects have been here a very long time – for hundreds of millions of years, and have thrived in every continent except Antarctica; in soil, air and water; in every habitat except the ocean. Insects lived on earth long before there were dinosaurs, and long after their disappearance. So why are such highly successful, highly evolved insects now disappearing?

The researchers in Germany, working across 62 nature reserves since 1989, found the annual average fell by 76% over their 27-year study period, but in summer, the drop was even more extreme – by 82%, when insect numbers should be at their peak!

The German entomologists have not laid the blame for these losses on any one issue, but it is probably safe to assume that man-made landscape changes, lack of food, and the use of pesticides and chemicals at an industrial scale have combined to make much of these German landscapes inhospitable to insects that thrived there for millennia until the 1980s.

Why are their findings anything new when compared to research on other endangered species? Because this level of insect loss – across varied families, genera and species, across insects with very different diets and lifestyles – shows a blanket loss of biodiversity – and is therefore thought to signal that all life on earth is on course for an ‘ecological Armageddon’. This is not a story about a single primate losing its home to palm oil plantations, this is widespread annihilation of countless species, in one go.

It is an important story because it is an indicator to how much we are changing the planet but also because insects are important – they are important as pollinators of our food, as the base of food chains for countless birds, bats and other mammals, and as predators who control other insect pests, and decomposers, which clean up dead matter.

Last June, I took on the role of Project Officer on the All-Ireland Pollinator Plan because its tenets struck me as something fundamental and extremely necessary. The Plan hinges on the belief that we must allow nature to have some space in our landscapes, that we have squeezed nature out through our constant tidying up, and ‘improving’ and spraying and mowing, and that for all our sakes, and for our food production and for the general health of our environment, it is now time to question the way we manage land, and to see if we can perhaps leave some space for nature once again.

Just like the German entomologists, ecologists in Irish universities and here in the National Biodiversity Data Centre, were measuring losses in bees and other insect populations over the past 30 years, and decided something should be done about it. The brainchild of Dr Úna FitzPatrick (National Biodiversity Data Centre) and Dr Jane Stout (TCD), the All-Ireland Pollinator Plan was born.

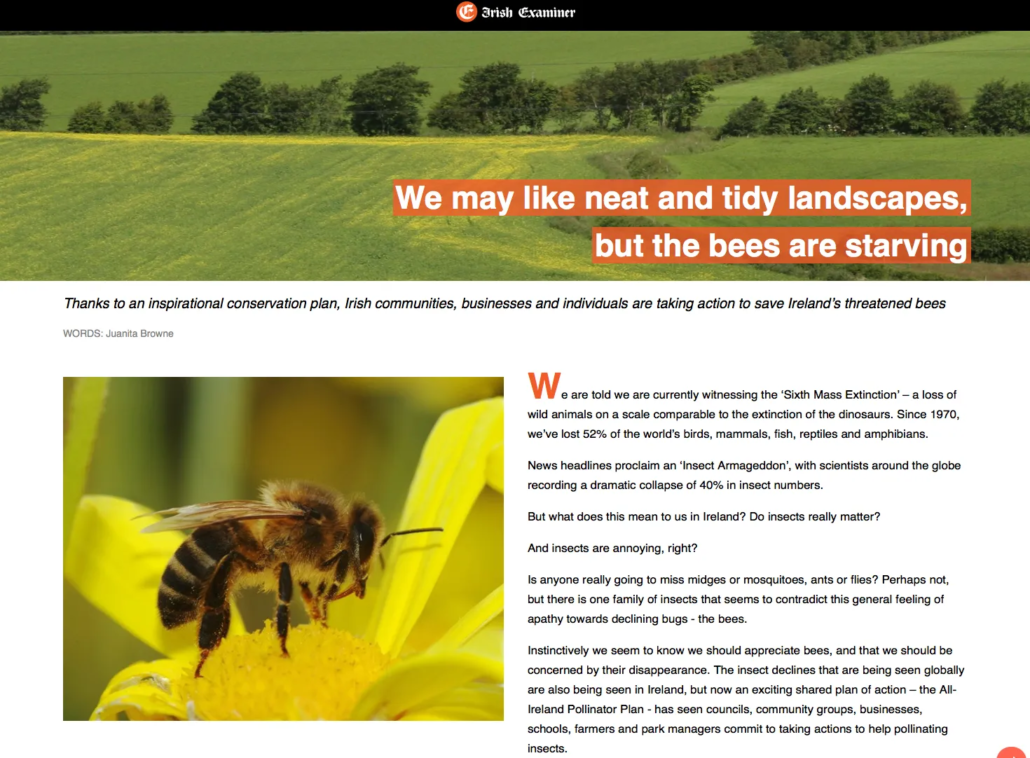

Take our bees… In Ireland, we have 99 species of bee: one honeybee; 21 Bumblebee species and 77 solitary bee species. Since the 1980s, over half of all these species have undergone huge declines and one-third are now threatened with extinction. So we see, this is not just a German problem.

Indeed, even my earlier windscreen story, it turns out is now a common anecdote and is now recognised as the ‘windscreen phenomenon’ among entomologists – we may already have been witnessing a loss in flying insect biomass here too.

The All-Ireland Pollinator Plan takes a very positive approach to nature conservation – it is a call to action, underpinned by the message that everyone can help – in our gardens, in schools, in local councils, on farmland and even in business.

A big challenge is spreading the word about insect losses and how we can all create more pollinator-friendly landscapes – by providing food, safety and shelter wherever possible. Most people don’t know that by allowing wildflowers to grow (such as Dandelions or clover), this will go a long way towards reversing declines in our pollinating insects. When people understand that our bees are actually starving, they do empathise and you can see them wondering what changes they can make on their own farm or in their garden to allow for more wildflowers.

We should all be grateful for research like this Plos One paper from Germany, which highlights changes that might otherwise go unseen. If a tree falls in a forest and there’s no one there to hear it, that doesn’t mean it hasn’t fallen. The Pollinator Plan is about telling people the trees are falling and let’s do something about it!

If we care about our ability to produce our food, we must care about pollinating insects. And if we care about wildlife and healthy ecological systems, we must care about the maintenance of all insect populations.

Ecologists are very conscious of always being the harbingers of more bad news, but I like to think that the All-Ireland Pollinator Plan, while, yes, communicates about our threatened bees, it also offers really positive actions and empowers everyone to make a difference.

– Juanita Browne, Project Officer, All-Ireland Pollinator Plan

To find out more about the All-Ireland Pollinator Plan, please see pollinators.ie

https://www.biodiversityireland.ie/where-have-all-the-insects-gone/

Biodiversity – A crisis in Ireland and globally

I care about Biodiversity.

I have always felt instinctively that Biodiversity has intrinsic value, that we should conserve all of the variety of life on Earth; that we have a responsibility to leave this planet and its catalogue of life as intact as we can when when each of us leave this place – to be enjoyed and celebrated, and to nourish future generations.

Economists have tried to put a monetary value on biodiversity: Ireland’s biodiversity contributes €2.6 billion each year to the Irish economy through ecosystem services. But on top of these tangible ecosystem services – such as water or air quality, soil fertility or pollination services – there are also other countless benefits of biodiversity such as human quality of life and mental health.

Ireland’s last Great Auk was killed in 1834, just 10 years before the entire species went extinct. Tragically, many species in Ireland and abroad are set to follow suit.

Walking by the trees on your street makes you feel good, hearing birdsong when we wake makes us feel good. Walking by a clean stream makes us feel good. Knowing you are not actively causing extinctions of species that have been here longer than us makes one feel good.

I have accepted that if I have great grandchildren some day, tigers may only exist in zoos or nature reserves, I accept that polar bears and gorillas are probably on the way out, drifting towards the cliff edge, towards extinction. Of course that is to say: I have accepted it, but it does make me very very sad. Some charismatic species will inevitably be lost as the global human population continues to explode and land pressures encroach on natural habitats. Saving those species in ‘the wild’ is a huge challenge I’m not sure that us humans are up to.

But what about the rest of our biodiversity – the lesser known reptiles, amphibians, birds, the thousands and thousands of plant and insect species that don’t make the headlines? What about the Crop Wild Relatives that give genetic stability to the crops we eat? What about the medicinal plants still to be discovered? Shouldn’t we try to conserve as much biodiversity as we possibly can?

The global statistics make disturbing reading: one of every four mammals is threatened with extinction; six out of every seven turtles!; one out of every three amphibians, one of every eight bird species. In Ireland, we know that of the species groups assessed, between one fifth and one quarter are threatened with extinction, too. The current rate of extinction is about 1,000 times higher than what it would be in the absence of human activity and exploitation. Wow. Take a minute to consider that… 1,000 times. What legacy is that?

In order to protect our giant bank of valuable unique species, we must first know what we have and where they exist. Having a robust catalogue of data on species allows us to track changes over time in species and habitats. We must have this robust scientific knowledge at our fingertips in order to feed into international conventions, nature protection legislation and national programmes to address biodiversity loss.

In 2002 the Irish Government committed to the establishment of an Irish biodiversity database and a national biological data management system in Ireland’s first National Biodiversity Plan, and five years later, in late 2007, the National Biodiversity Data Centre was established.

“The overarching mission of the National Biodiversity Data Centre is to provide national coordination and standards of biodiversity data and recording, assist the mainstreaming of biodiversity data and information into decision-making, planning, conservation management and research, and encourage greater engagement by society in documenting and appreciating biodiversity.”

The National Biodiversity Data Centre acts as a repository for data coming from researchers, wildlife groups, and citizen scientists all over Ireland. It is a safe place to send your records where your data will be conserved forever, instead of rotting away in notebooks or on an old PC. Your data can feed into national policies and management regimes and ultimately help to conserve our precious biodiversity.

The Data Centre currently stores more than 4 million records of over 16,000 speces.

The data held by the Data Centre doesn’t just help to contribute to decision-making in Ireland, it also feeds into international conservation initiatives. For example, the Data Centre’s Butterfly monitoring schemes feed into European butterfly atlases that can identifiy species range changes, changes in emergence times, and help to suggest causes of declines.

Of course, nature doesn’t recognise country borders. Swallows that arrive in Ireland to breed every summer have flown here all the way from Africa. Many of our species have this international aspect and with human travel and imports bringing invasive species to our shores on a regular basis, there is a clear need for countries to work together and share data to build a global biodiversity data network.

That network is the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, GBIF, a network of 57 participant countries, that holds over 1 billion species records.

Over 1.9 million records of Ireland’s biodiversity are published through GBIF. This includes records from 725 different datasets published from 31 different counties.

It’s amazing to think that my humble record of a butterfly in my garden, logged on my mobile phone through the Data Centre’s mobile app, will eventually find its way to this global biodiversity network and can be accessed by scientists anywhere in the world.

So I’m really excited about an event happening this October, when GBIF delegates from all over the world are coming all the way to Kilkenny for their annual meeting. Previous meetings have been held in Madagascar, in the Ivory Coast, in New Delhi, in Finland. So it is a huge honour for Ireland to host this meeting in Kilkenny in 2018. I’m proud to learn that Ireland is at the centre of everything when it comes to this global biodiversity infrastructure, that within GBIF, we are held up as an exemplary country in our management of our biodiversity data, our work standards, and now that Ireland is hosting this important event.

On October 18th, a public symposium will allow us all to learn more about the importance of biological recording on a global and national scale. Why not come along and hear how biodiversity data is managed on a global scale and some of the ways that participant countries, including Ireland, use that data to inform conservation?

When my nephew turns off his X-box, a pop-up screen says “Whatever is not saved will be lost.”

Perhaps we could say the same for our biodiversity. We must try. We must research, record, try to understand, share our information with others, and ultimately we must try to save all that we can.

18th October 2018: Biodiversity loss in a changing world: local data, global action

The National Biodiversity Data Centre is delighted to host the 25th meeting of the Governing Board of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) in Kilkenny from 15th to 18th October, 2018. The event will see delegates from 57 Participant Countries and 36 other Associate Participants across the world attend the Governing Board meeting.

On Thursday 18th October, the National Biodiversity Data Centre is hosting a public symposium Biodiversity loss in a changing world: local data, global action which provides a unique opportunity to hear about some of GBIF’s work and its global network. There will be keynote addresses from Donald Hobern, Executive Secretary of GBIF and Dr Thomas Orrell of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, in addition to speakers talking about how data are used to inform biodiversity action at a regional and national level. Speakers from Ireland will outline a number of use cases where data is used to better inform policy and encourage greater local community engagement.

– Juanita Browne works on the All-Ireland Pollinator Plan.

Why we all need to care about saving Ireland’s starving bees, Irish Examiner

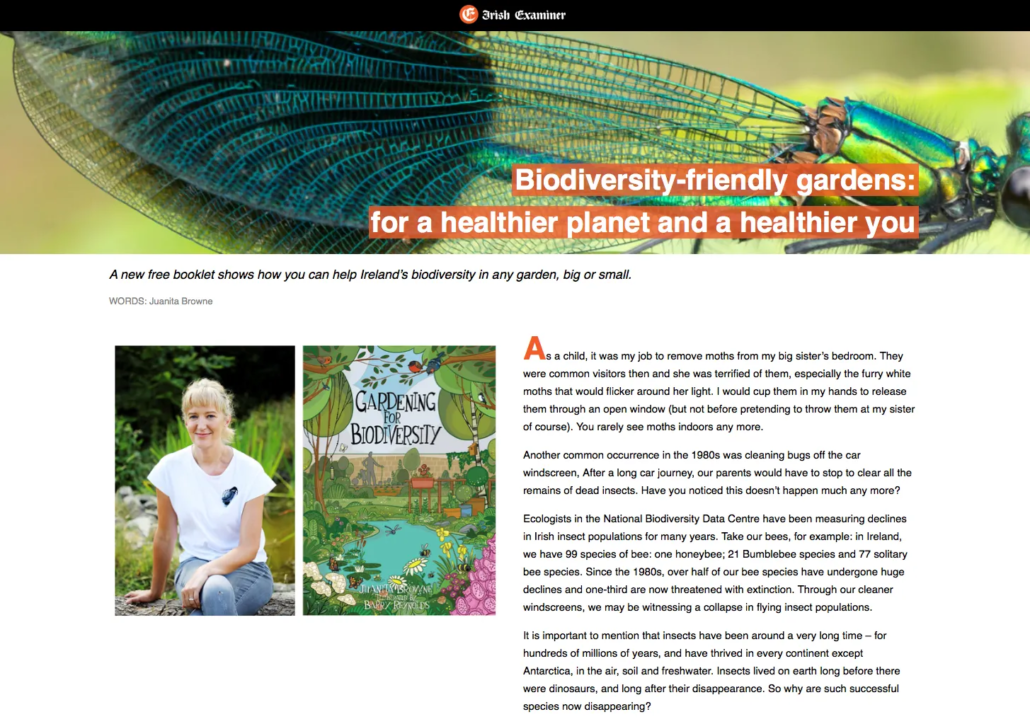

Biodiversity-friendly gardens – for a healthier planet and a healthier you